A Flood of Emotions: A Valentine’s Atmospheric River and Avalanche Cycle

In the days leading up to Valentine’s Day 2025, Colorado’s snowpack was primed for an avalanche cycle. When an atmospheric river slammed into Colorado on February 13 with multiple periods of high-intensity snowfall, the avalanche danger quickly increased statewide for two weeks. A major avalanche cycle ensued during and immediately after the storm, resulting in several close calls and, tragically, two people were killed in avalanches.

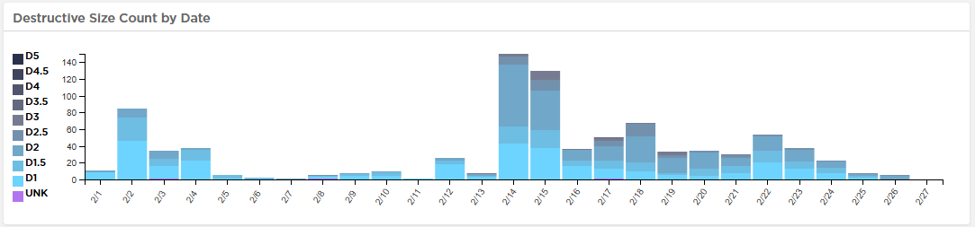

The storm started as a statewide event but eventually favored the Northern Mountains. Favored areas in each region reached HIGH (4 of 5) avalanche danger on Valentine’s Day. In some areas, the danger increased two levels from February 13 to 14. Some areas returned to HIGH (4 of 5) danger on February 17. At least one zone was rated at CONSIDERABLE (3 of 5) or higher from February 12 to March 2.

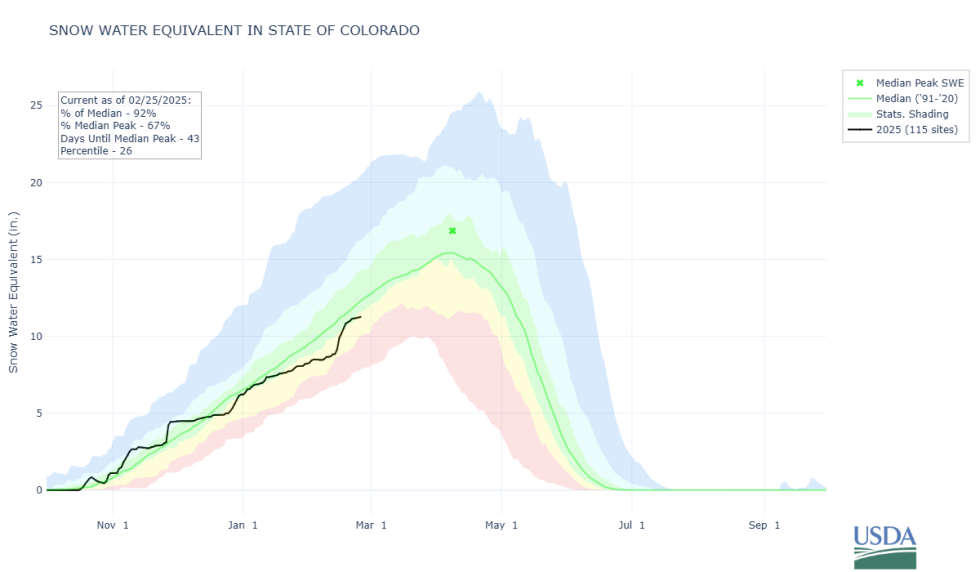

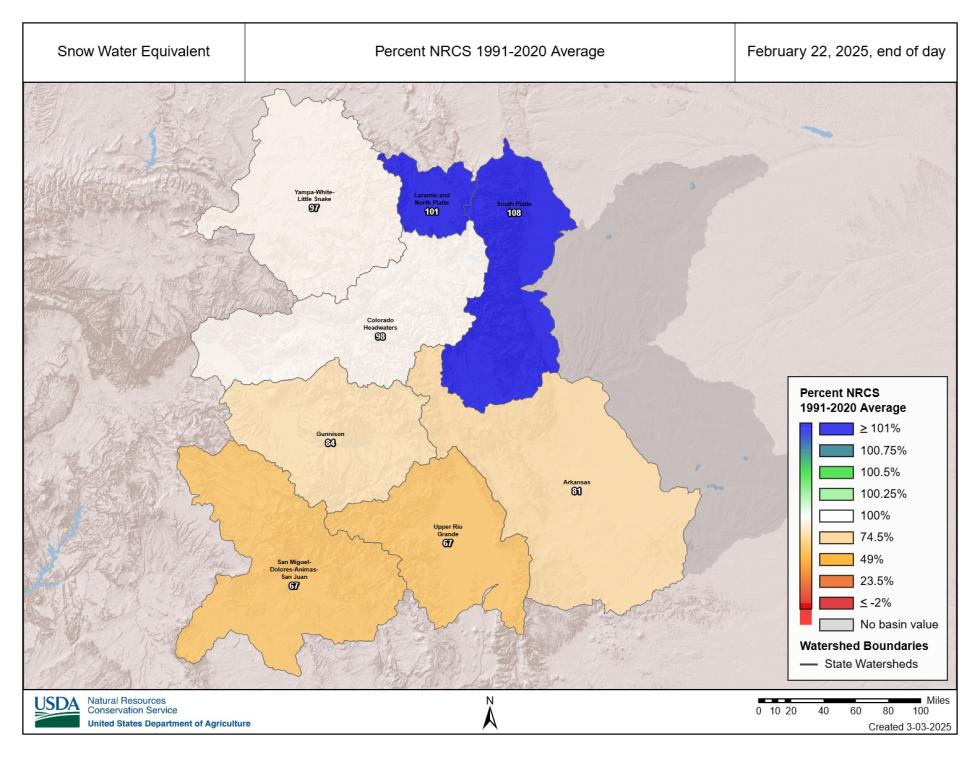

From February 12 to February 22, most areas saw 2 to 4 inches of snow water equivalent (SWE). The higher totals favored the Northern and Central Mountains, with a few areas even breaking the 5-inch SWE mark. Although none of the weather stations in the Southern Mountains recorded 4 inches of SWE, many reached the 2.5 to 3.5 range. Given the impressive snow totals statewide and a snowpack containing multiple weak layers, it was no surprise that a major avalanche cycle ensued and that dangerous avalanche conditions persisted for weeks.

The new snow quickly formed a thick slab of snow, and signs of instability, such as cracking and collapsing, decreased quickly. While some backcountry travelers stepped into consequential terrain without issue, the number of avalanches and involvements told a different story. A cycle of large to very large (D2-3) avalanches breaking across multiple terrain features started immediately, signaling dangerous conditions. Notably, many avalanches–especially in the Northern Mountains–broke near the ground.

Statewide, from February 12 to February 22, more than 50% of reported avalanches were large enough to bury or kill a person, and we continued to see large and very large avalanches up to two weeks after the storm. During and immediately after the storm, there were a number of close calls in the backcountry. One notable accident where the victim survived was near Vail Pass, where a snowmobiler was buried for about an hour before rescuers located him. Another was near Telluride Ski Resort where a sidecountry rider triggered a very large (D3) avalanche that carried him more than 1000 vertical feet, including over cliffs. In total, 15 people were caught in slides from February 12 to February 22. Unfortunately, two of those accidents were fatal, one in the Southern Mountains near Silverton and the other in the Northern Mountains near Berthoud Pass. Both slides broke several feet deep across multiple terrain features, presumably without warning. Our condolences go out to the family and friends of the victims and anyone else involved.

A Tender Heart: A Snowpack on the Edge Heading into February

Even though there was a major storm and avalanche cycle around Thanksgiving, by late December, the snowpack was mostly faceted. Although there was plenty of weak snow, there was no slab and thus very few avalanches. The late December to early January storm–ending on January 6–deposited a thick, dense slab of snow on top of this weak base. This “December Drought” interface became the primary weak layer of concern, and our second major avalanche cycle of the winter took place.

January was defined by a consistent series of short-lived storms that favored the Northern, and sometimes Central, Mountains. A blast of subzero temperatures combined with dry weather in the middle of January formed another weak layer. While this layer was less reactive and widespread than the December Drought layer, forecasters' focus started to shift to upper snowpack issues as the December Drought layer became less reactive by the end of January. Although the consistent storms with intense winds kept reports of avalanches trickling in, most avalanche activity was associated with new snow or breaking on weak layers buried in January.

Multiple days of unseasonably warm temperatures in early February put an end to new snow problems and resulted in a wet snow avalanche cycle. By February 5, the entire Southern Mountains and a couple of areas in the Northern and Central Mountains dropped to LOW (1 of 5) danger. A storm with strong winds the second week of February created a patchwork of surface conditions across the state and resulted in two surprising avalanches in the Northern Mountains. One was near Cameron Pass, and the other near Vail Pass. Both slides stepped down to the weak December Drought layers, exposing the ground in places, the first slides to do so in a couple of weeks. Looking back, these avalanches were a preview for what was to come.